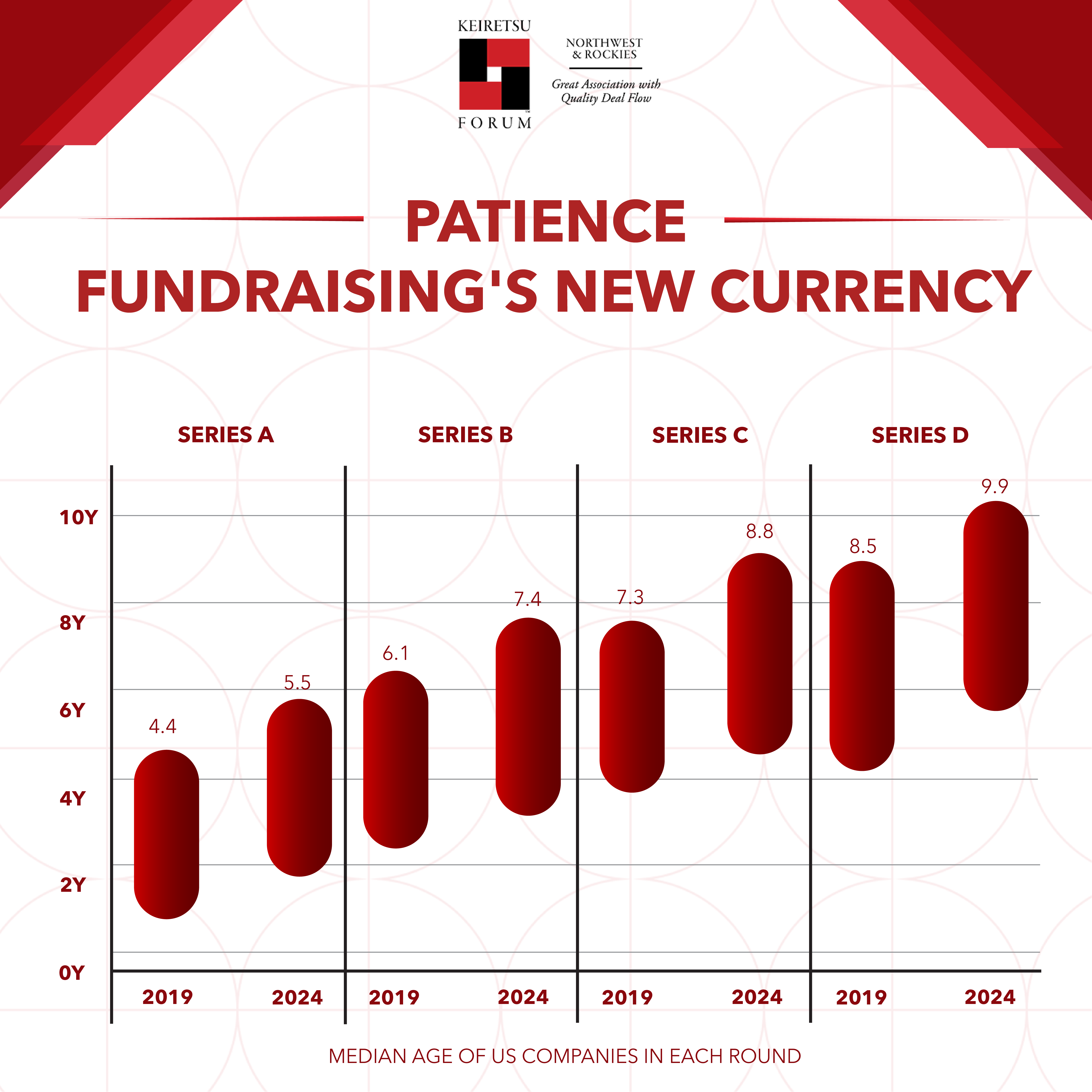

Fast and Furious – This is what the early stages of a company used to look like. A blitzkrieg from seed to Series B, followed by a patient buildup of something more substantial and long-lasting with more investors on the table. In the last five years, however, companies have become more cautious in moving to each funding round. The blitzkrieg is replaced by a careful and methodical approach, which has ultimately increased the median company age in every funding round.

Carta’s October 2024 Data Minute newsletter, analyzing US startups from 2019 to Q3 2024, suggests that companies are raising each successive funding round at a later stage in their lifecycle. In 2019, the median age of companies raising a Series A was 2.6 years. By 2024, that figure had grown to 3.5 years. And it’s not just Series A, this trend holds across every major round. Seed rounds have shifted from a median of 1.3 years in 2019 to 1.9 years in 2024. Series B now arrives at 5.5 years (up from 4.7), Series C at 6.9 (up from 6.4), and Series D has stretched from 6.9 to 8.3 years.

This isn’t just statistical noise. It’s a meaningful shift in a business’s journey. So what’s driving this evolution?

The Rise of Convertible Instruments

One major factor is the increased reliance on convertible instruments, such as SAFEs and notes. Over the past few years, it has become common for companies to raise two, three, or even four rounds of unpriced capital before ever facing a priced equity event.

This flexibility has made it easier for founders to access capital earlier without setting a valuation. However, it also delays the moment when a company formally enters the "seed" stage on paper, making companies appear older by the time they raise what is technically their first priced round. What used to be called a seed round may now follow years of product development, team building, and traction gathering.

The result? The timeline for a priced seed and all subsequent rounds has been extended.

Fundraising Now Takes 2x Longer or More!

Another obvious catalyst is the recent funding slowdown. The funding landscape has cooled dramatically since 2021. Investors became more selective, valuation expectations were recalibrated, and diligence processes deepened.

For companies, this meant longer runways and longer waits between raises. A company that might have raised its Series B just 12–18 months after its Series A in 2020 may now be waiting 24–36 months to hit the same milestone. These delays compound over time, resulting in companies reaching Series D at a significantly older age.

In short, the pace has slowed, but not necessarily the ambition.

Fewer IPOs, Longer Private Journeys

The shift is also tied to a larger macro trend: companies are staying private for longer periods. The public markets have not been kind to newly listed tech companies in recent years. Many late-stage companies have responded by postponing their IPOs and pursuing alternative paths, such as secondaries, growth rounds, or M&A.

This hesitancy to go public means companies remain in the private markets for longer periods. The median age of companies going public has steadily climbed, often crossing the 10-year mark. For founders and investors alike, this changes the long-term expectations: liquidity may be further away, but value creation can still occur in the private domain.

So What Does This Mean? Is It Good or Bad?

The key takeaway is clear: the startup journey is getting longer. What used to be a 6- to 8-year path from seed to exit may now take a decade or more. Building a company was never a sprint, but now it’s more of an endurance game than ever.

As a founder, you are expected to recalibrate your expectations and strategy. Use the time gaps to build a better product or service and a more efficient team that is ready to deliver in the later stages of the company. This patience can lead to stronger, more sustainable businesses in many ways.

If you are an investor, this timeline shift affects everything from fund construction to return expectations. It may also open up new opportunities, such as later-stage secondaries, longer-term investments in mature but still-private companies, and alternative liquidity mechanisms.

Companies aren’t getting old in spirit; they’re just taking longer to mature.